Community Forest Rights Mapping: Field School

Smart Forests field schools were conducted in the village of Kunao Chaur, Uttarakhand, India , in two phases. The initial phase took place in December 2022, followed by the second phase in January 2023. These field schools were specifically designed to investigate the socio-political dynamics emerging from the use of digital technologies for mapping indigenous forest rights and biodiversity . These field schools were part of a larger Smart Forests case study project that aims to explore how the Van Gujjars, a traditional semi-nomadic and forest-dwelling community, interact with digital technologies traditionally used for conservation . This interaction includes recording their own knowledge, sense of place, and space, and engaging in counter-mapping activities.

During the first phase, Smart Forest researchers organized a field school to discuss the role of aerial monitoring technologies, such as drones , in mapping forest rights, monitoring biodiversity, and observing land use changes as perceived by the Van Gujjar community. Participants included male members of the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan, a collective that advocates for social issues, rights, and justice for the Van Gujjars. Male elders, referred to as ‘Lamberdars’ (heads of families), also participated in the discussions. Due to logistical and cultural constraints, women from the community were not involved in this phase. Research indicates that intersectional markers such as gender, class, caste, and disability are crucial variables through which digital technologies should be examined. To address this, a subsequent field school was conducted in February 2024, which included women participants.

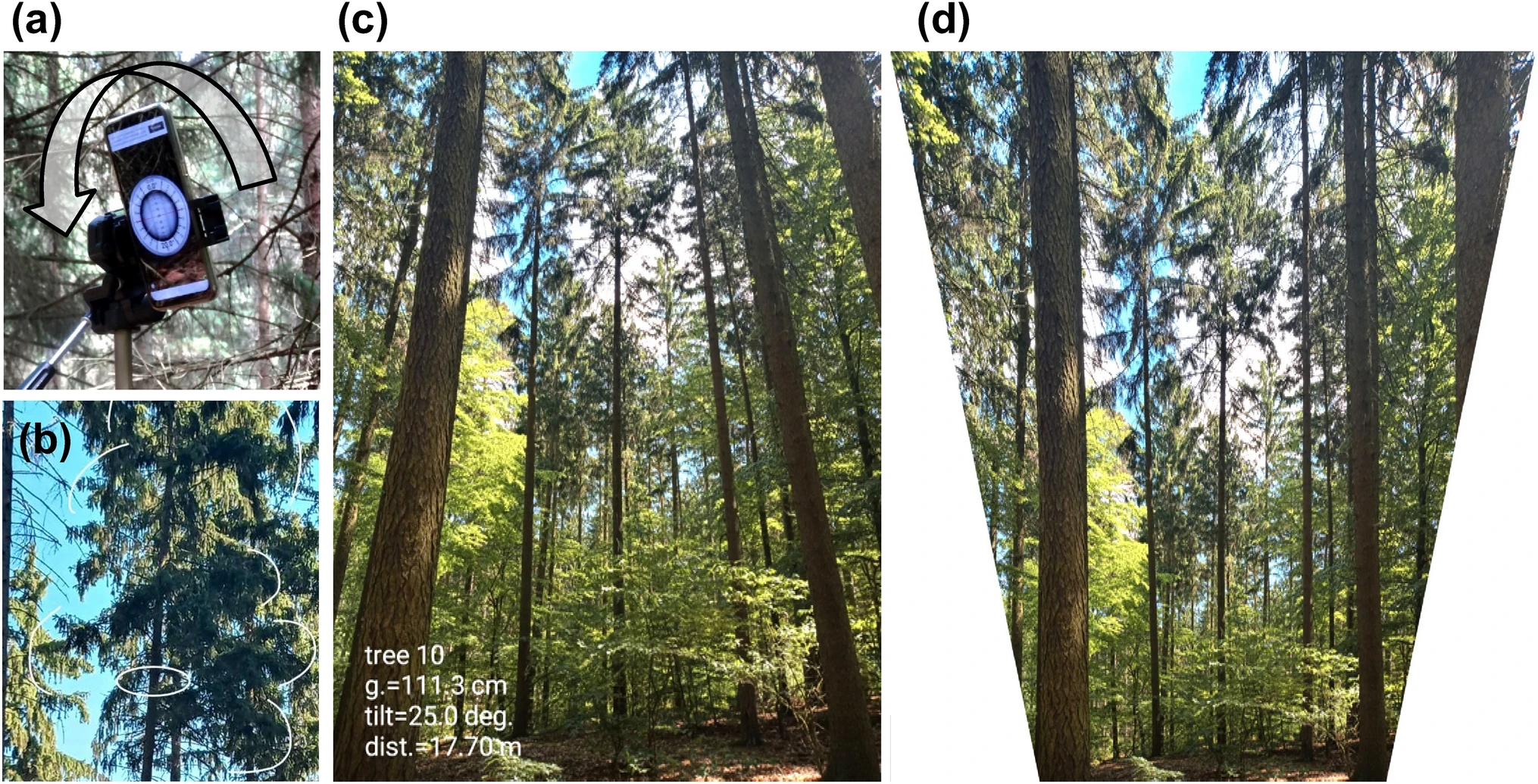

During the morning session of the field school, Smart Forest researchers engaged in a participatory discussion and workshop on the correct usage of GPS devices for mapping forests and other biodiversity features relevant to the community. Pranav Menon, a collaborator from Smart Forests, presented the basics of global positioning systems, including how to correctly mark waypoints and transfer data onto a laptop. Community members then discussed important features that needed mapping, which would generate knowledge to support their forest rights claims. For instance, some members immediately identified certain parts of the forest that were previously plantations or grasslands (‘bhabars’) where they were historically permitted by the colonial state to graze their cattle. During the demonstrations, several immediate challenges were highlighted. Due to disputes over land and forest access rights between the state forest department and community members, concerns were raised about potential harassment by forest rangers if they were found with GPS devices in the forest. Despite the long history of exploitation and dispossession of forest-dwelling communities in India (Sigamani, 2015), community members have begun to resist and subvert state excesses. They expressed that, despite the practical difficulties of using these devices, it was still significant to possess the ability to create their own knowledge.

Pravan presenting on GPS systems.

The second session of the field school included a participatory discussion and workshop on using digital technologies for real-time aerial monitoring. Smart Forest researchers presented the use of drones in biodiversity conservation, highlighting the opportunities and associated risks. Community members expressed how drones were used by the state forest department to monitor their settlements and occasionally create panic among their grazing cattle. This coercive practice has been documented previously in the Corbett Tiger Reserve, under the same state government (Simlai, 2022). During the demonstration, community members pointed out how drones could be used to monitor their own cattle, document the spread of invasive weeds like ‘lantana’ on their grazing lands, and photograph cultural markers and biodiversity features from an aerial perspective to substantiate their forest rights claims. It was acknowledged that using drones in their context was nearly impossible, except in areas where forest rights were settled, due to the risk of persecution by the state forest department. Researchers also observed that the flying drone triggered excitement among members, with many requesting it to be flown over their houses or near children to shock or scare them. This practice was discouraged, and the associated risks were discussed with community members. These observations underscore the importance of regulation when using digital technologies, even with Indigenous communities , as power imbalances and other social markers may influence drone usage.

Aerial View of a Van Gujjar Settlement.

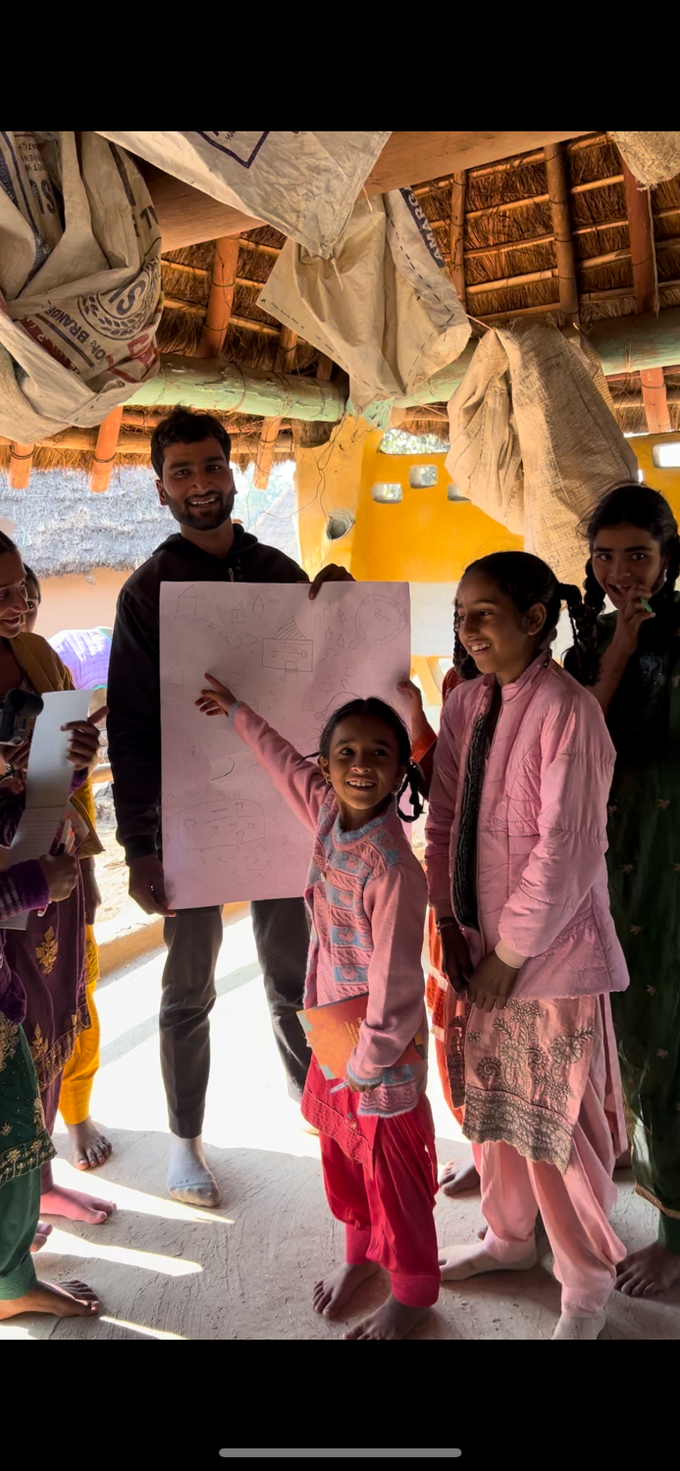

The second phase of the Smart Forests field school took place in January 2023 in the village of Kathiyari, Uttarakhand, India. A workshop was conducted by Smart Forest researchers in collaboration with the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan (VGTS), involving a diverse group of stakeholders among the Van Gujjars, including family patriarchs, women, and children. The objective of this field school was to understand how the Van Gujjars perceive the forest spaces they use and inhabit, and how their maps, referred to as ‘nazri naksha’ (perceived maps), differ from or resemble digital mapping with GPS systems. Participants were provided with chart paper and sketch pens to illustrate forest areas used for activities such as cattle grazing, forest produce collection, and wildlife encounters. A diverse range of maps was created, varying according to the social group involved in the mapping. For example, children who accompanied elder grazing men or women highlighted forest areas used as playgrounds or areas avoided due to frequent elephant activity. Women mapped forest paths used for collecting fresh grass as fodder for their cattle.

Children showing mapped features.

After the exercise of mapping on paper, a practical demonstration was conducted where community members walked in the forest with GPS devices to map biodiversity features. Smart Forest researchers noted that community members made diverse observations and recorded aspects often overlooked in large mapping projects associated with conservation. For instance, community members mapped graves and points of interest such as locations where elephants once grazed and identified trees useful to them. During the post-demonstration discussion, community members decided to always start with mapping on paper before engaging in field mapping. This approach ensures that community members remain consistent with their perceived sense of space while mapping digitally. Participants observed that more biodiversity, terrain, cultural, and topographical features were mapped when creating visual maps on paper, whereas walking with a GPS in the forest somewhat restricted their mapping sense.

Visual Mapping on paper.

Smart Forests field schools in Uttarakhand exemplify the intricate interplay between digital technologies and traditional forest-dwelling communities. By integrating modern tools such as drones and GPS devices, the Van Gujjars were empowering themselves to document and assert their forest rights more effectively. These technologies facilitated the creation of detailed maps and counter-mapping activities, enhancing their ability to articulate and defend their knowledge and territorial claims against external pressures. However, the field schools also highlighted the socio-political challenges and power imbalances inherent in the use of such technologies. The exclusion of women in initial phases and the potential for harassment by state authorities underscore the need for inclusive and context-sensitive approaches. Overall, these initiatives reveal the dual potential of digital technologies to both empower and challenge Indigenous communities, stressing the importance of mindful implementation that considers cultural, gender, and power dynamics.

Sigamany, I., 2015. Destroying a way of life: The Forest Rights Act of India and land dispossession of indigenous peoples. In Development-Induced Displacement and Resettlement (pp. 159-169). Routledge.

Simlai, T., 2022. Negotiating the Panoptic Gaze: People, Power and Conservation Surveillance in the Corbett Tiger Reserve (Doctoral dissertation).

Smart Forests Atlas materials are free to use for non-commercial purposes (with attribution) under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. To cite this story: Simlai, Trishant, "Community Forest Rights Mapping: Field School", Smart Forests Atlas (2024), https://atlas.smartforests.net/en/stories/community-forest-rights-mapping-field-school/. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.13902973.